A Dane, a Norwegian, and a Swede went to the bank in their respective countries to take out a housing loan during a period characterized by low interest rates. What happened when interest rates began to rise?

Kjetil Olsen, chief economist at Nordea in Norway, has investigated the question and found that the Swede is by far the most interest-rate sensitive borrower.

The Dane doesn't have to worry much since most have annuity loans with a fixed interest rate for 30 years.

Extremely interest-rate sensitive

The majority of Norwegians also have 30-year annuity loans, but unlike Denmark, most have variable interest rates.

The annuity principle is that you pay a fixed amount each month for interest and amortization together. If interest rates rise, you pay less in amortization. If interest rates fall, you pay more in amortization.

In Sweden, the standard is straight amortization, so-called serial loans, with variable interest rates or fixed interest rates for a shorter period. When interest rates rise, the consequence is that the entire interest burden is directly transferred to the borrowers' wallets, according to Olsen.

Norwegians are still quite interest-rate sensitive, but Swedes are extremely interest-rate sensitive because they have serial loans.

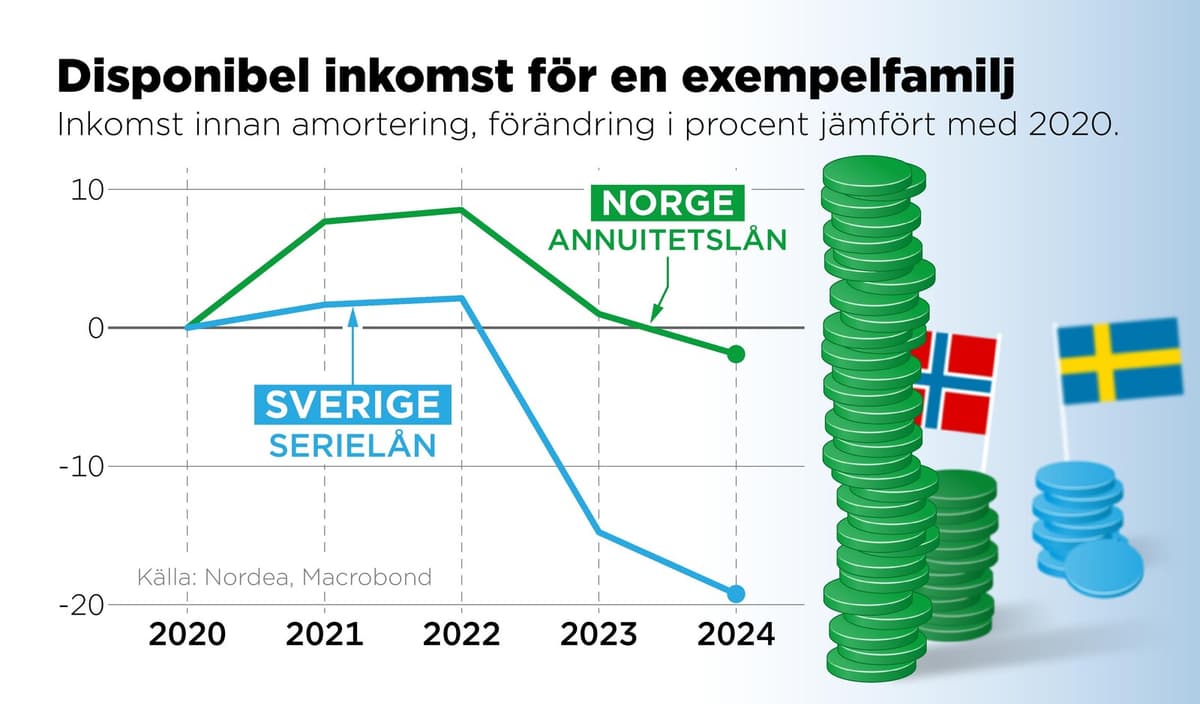

The respective mortgage systems have had a direct impact on the countries' economic growth, as shown by data compiled by Olsen.

Sweden's growth has been worse than both Denmark's and Norway's.

"Very good system"

An indication of this is that Swedes have spent significantly less than both Norwegians and Danes on services.

Norway is far above the level we had before the pandemic. In Sweden, it's below. In Norway, people have been so disappointed that interest rates have risen, but they don't understand how bad it can actually be, says Olsen, referring to Sweden.

But the positive news is that Sweden will get a pretty good "boost" when the Swedish Central Bank lowers interest rates. I would guess that 2025 will be better.

Denmark also has a unique system – but in a positive sense, according to Helge Pedersen, chief economist at Nordea in Denmark. Homeowners with real credit loans financed through bonds can convert their loans at any time, which means they can sell their debt and renegotiate the interest rate.

It's a very good system that can be utilized privately, says Pedersen.

In Norway, the majority have annuity loans with variable interest rates. An annuity loan is a loan form where the borrower pays a fixed amount at each payment, which includes both interest and amortization. At the beginning of the loan period, a larger part of the interest and a smaller part of the amortization.

In Sweden, the majority have serial loans, straight amortization, with variable interest rates or fixed interest rates for a shorter period. Serial loans are a loan form where the amortization is a fixed amount at each payment. In addition to amortization, the borrower pays interest on the remaining part of the loan. The fee is generally higher at the beginning of the loan period.

In Denmark, a large part has real credit loans, which are financed by a real credit institution that issues bonds. The security for the loan is the home itself. The interest rate on the loan is usually fixed for 30 years. Furthermore, borrowers with real credit loans can convert their loans at any time, which is called conversion. The value of the debt decreases when interest rates rise. Conversely, the value of the debt increases when interest rates fall. Those who have converted their loans in recent years have been able to reduce their housing debt by up to 30 percent while getting a higher interest rate. It is also possible to convert in the opposite direction, which means that the debt increases while the interest rate decreases. In addition to real credit loans, there are amortization-free bank loans without the possibility of conversion.

Source: Nordea, Øresunddirekt, Realkredit Danmark / Danskebank