A murmur went through the trading room at major bank SEB when the unexpectedly high inflation figure appeared on the screens, according to Amanda Sundström, interest rate strategist at SEB.

It's a very clear movement. The market is adjusting, she says about the reactions.

The krona is strengthening and market interest rates are rising. The probability of future interest rate cuts is also clearly decreasing in pricing.

"I think it's temporary"

The Swedish Central Bank – which has 2.0 percent as its inflation target – lowered the repo rate to 2.25 percent in January. The message from the board then was that no further cuts were expected in the near future.

The Swedish Central Bank will likely feel strengthened in its message by this figure, says Susanne Spector at Danske Bank.

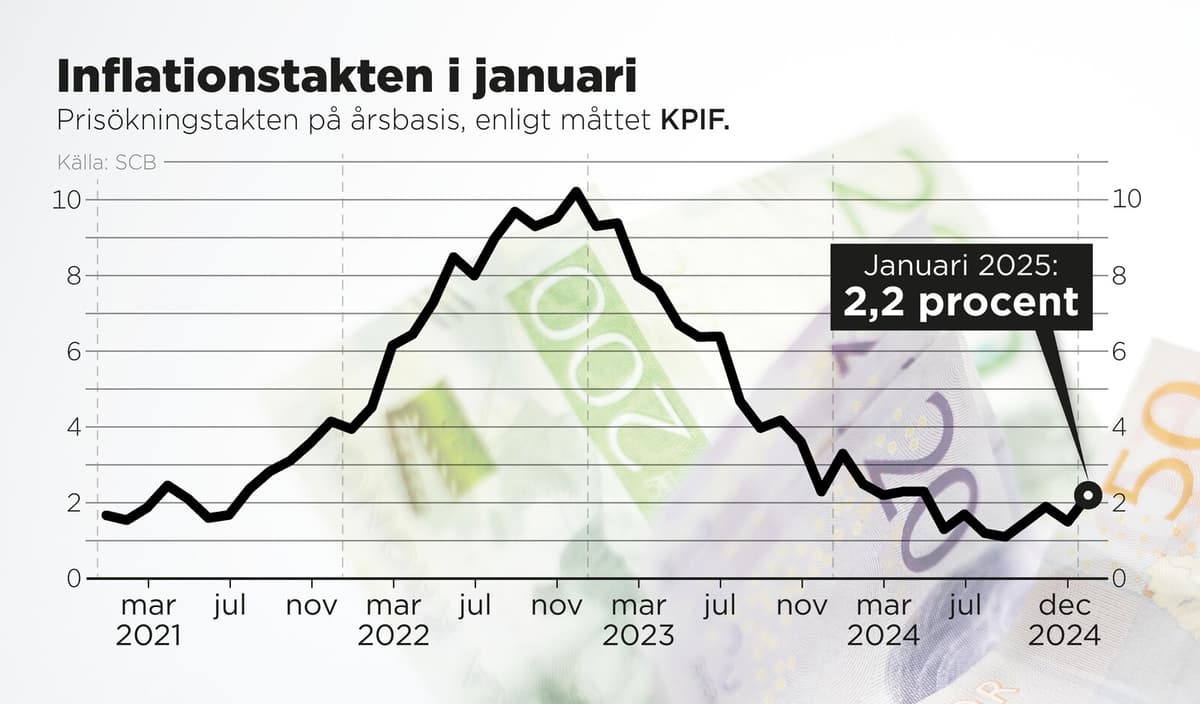

The inflation increase to 2.2 percent can be compared to 1.5 percent in December and an expected increase to 1.6 percent.

It's surprising. Then again, this is a quick figure and we don't have the details, which means we can't say exactly what it's due to, says Alexandra Stråberg, chief economist at Länsförsäkringar.

It could be energy prices or food prices that are causing the increase – but it's impossible to say at present, according to Stråberg.

I think it's temporary. We've been around an inflation rate of 2 percent, so we shouldn't overinterpret the monthly figure, especially not before we have all the details.

SEB's Sundström points to several factors that make the January figure difficult to interpret. For example, Statistics Sweden is using a new basket of goods. Moreover, many fee increases at the turn of the year may be affecting the figure.

The Swedish Central Bank may also choose to look through technical factors, if it's not really about higher price pressure, she says.

She does not rule out revisions either.

More details next week

More details explaining the inflation increase are expected next week, when Statistics Sweden presents a complete inflation report for January.

Spector at Danske Bank thinks the inflation increase looks broad, as it affects both excluding and including energy prices. But that the Swedish Central Bank would soon need to make a complete U-turn and start tightening with rate hikes again – to get inflation down – she does not see as likely.

It feels far away. The economic recovery is weak. The labor market is still developing in the wrong direction. Rate hikes in this situation are hard to see. But of course, nothing can be ruled out in the long run, says Spector.

Inflation in January rose to 2.2 percent according to the KPIF measure, up from 1.5 percent in December. Analysts had on average expected an increase to 1.6 percent.

In the KPIF measure, which the Swedish Central Bank formally uses as a benchmark for its 2.0 percent inflation target, the effects of mortgage rates have been excluded. If mortgage rates are included, and the KPI measure is looked at, inflation in January rose to 1.0 percent, up from 0.8 percent.

The underlying inflation rate – where both mortgage rates and energy prices have been excluded – rose to 2.7 percent in January. That measure was at 2.1 percent in December.