When the bright pink sea pig was seen wandering around on the seabed, several thousand meters down in the depths, on the screens in the research vessel's control room, cheers erupted.

It's not unusual to find new species in the deep sea. But when you discover a creature like this, you're amazed, says Thomas Dahlgren, researcher in marine ecology at the University of Gothenburg and the research center Norce in Bergen.

He participated in the 45-day expedition in the spring in the Pacific Ocean between Mexico and Hawaii, led by British researchers. The purpose was to explore life between 3,500 and 5,500 meters deep – which is largely still a mystery.

Record-long life

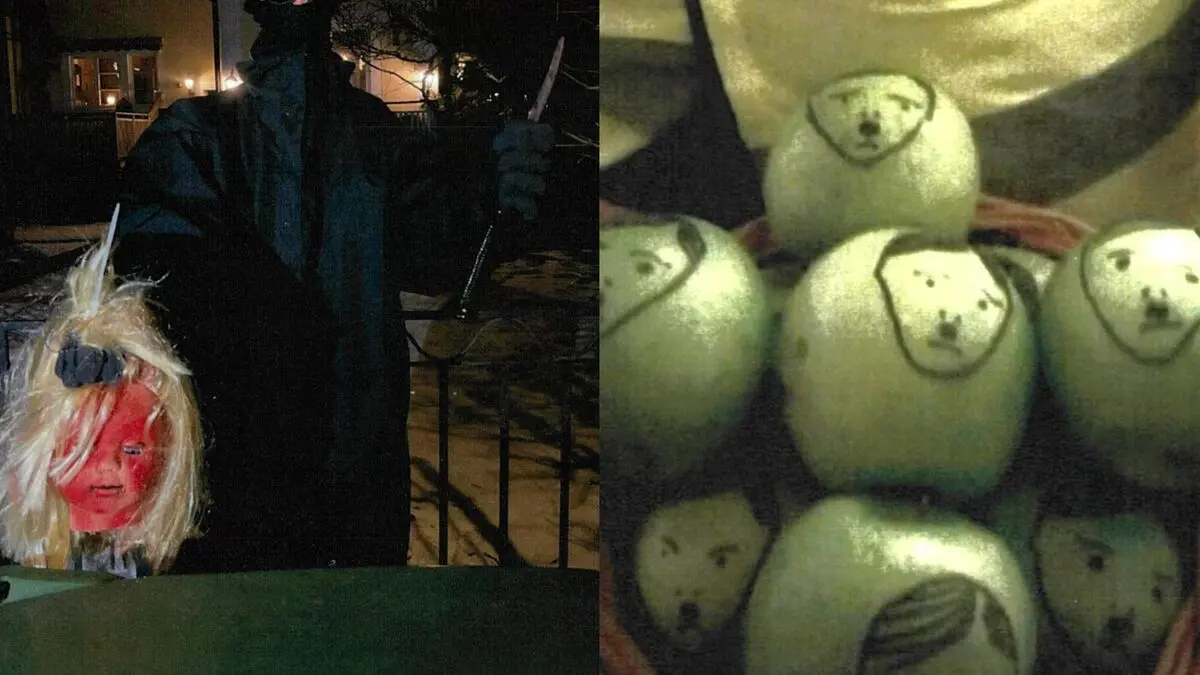

In addition to the pink creature that the British call the "Barbie sea pig", the researchers picked up a transparent sea cucumber and a funnel-shaped animal with the longest known lifespan on Earth, 15,000 years – and an estimated thousands of other species.

Work is now underway to identify the species, but it's certain that many of them will be surprises. Nine out of ten species taken from the deep sea are unknown to science, says Thomas Dahlgren.

Although these deep-sea plains are the most common environment on Earth, covering more than half of the planet's surface, interest in exploring them has been limited.

Until now. Countries and companies are now turning their attention to the seabed in search of rare metals for solar cells, batteries, and other green technology. Therefore, it's urgent for researchers to understand what lives in the depths – before it's too late. Several companies are on the starting line, not least for mining in the so-called Clarion-Clipperton zone where the expedition took place in the spring.

Potato-sized lumps

The mining companies want to extract potato-sized lumps containing metals such as cobalt, nickel, copper, and manganese, which are in high demand.

Both researchers and environmental organizations warn that deep-sea mining would harm ecosystems and biodiversity. The question is how much.

Before the International Seabed Authority (ISA) can give the green light for mining, it's essential to understand more. Last year, a study showed that nearly 5,000 new species were found in the Clarion-Clipperton zone.

Today, a third of the area is protected. But whether it's enough to prevent the extinction of species in the event of mining is unclear, according to researchers.

Materials for medicines

Besides being important components of the ocean's ecosystem, these species could come in handy for humanity, for example, for future medicines, emphasizes Thomas Dahlgren.

There's still so much to discover and research.

During the expedition in the spring, for example, sea cucumbers were found completely free of epibionts, which could indicate the presence of substances with antibiotic properties.

It's on our "to-do list" to investigate further, says Dahlgren.

Today, there is a temporary ban on deep-sea mining, but it can change with a regulatory framework that the ISA is now developing.

At the same time, there are concerns that mining will begin in the next few years before we have full knowledge of the consequences.

Therefore, it's essential that the regulatory framework is based on knowledge about the effects of mining technology on the environment and on species and ecosystems in the deep sea, says Thomas Dahlgren.

Plans for mining at sea also exist in our neighboring region. In Norway, the government has said yes to opening the country's seabed for possible exploitation, if the negative environmental effects are limited. This despite harsh international criticism, including from the EU Parliament.

Extraction in the Baltic Sea

There are also plans in Sweden to extract lumps containing metals from the seabed, although it's not deep-sea mining. The company Scandinavian Ocean Minerals has exploration permits for two areas in the Gulf of Bothnia, and researchers are mapping the consequences.

But Dahlgren sees it as out of the question to extract metals in the Baltic Sea, which is already heavily affected by eutrophication, bottom death, and overfishing.

As a biologist, I see no chance in the world of getting permission to do it in bottoms that are already full of pollutants, and considering that the Baltic Sea is already struggling.

The deep sea is believed to be the largest ecosystem on Earth, but it's the least explored.

There are also areas rich in metals such as nickel, copper, manganese, and cobalt. Extraction could be done in three ways:

Lumps, called nodules, containing various metals are sucked up from the seabed, sometimes at 5,000 meters deep, and taken up via large pipes.

Crusts that exist on slopes and mountains in the ocean and are rich in cobalt are "scraped" off.

Sediments that exist at hot springs along oceanic ridges and are rich in minerals are "scraped" up from the bottom.

Source: UI, Thomas Dahlgren.