About 355 million years ago, a small lizard-like creature walked along the riverbank. After a brief rain shower, another species came in the opposite direction, leaving fairly deep tracks in the sand. Then another one came.

it's a bit later in the day, it has started to dry a bit, so the tracks are not as clear. Moreover, the animal was in a hurry, so the claws have left long scratches, says Per Ahlberg, professor at Uppsala University and one of the tracks.

Later, the dried-up tracks were covered with sediment and buried. After eons of time, they emerged in a sandstone block just outside Melbourne, Australia, discovered by a happy amateur.

"Clear claws"

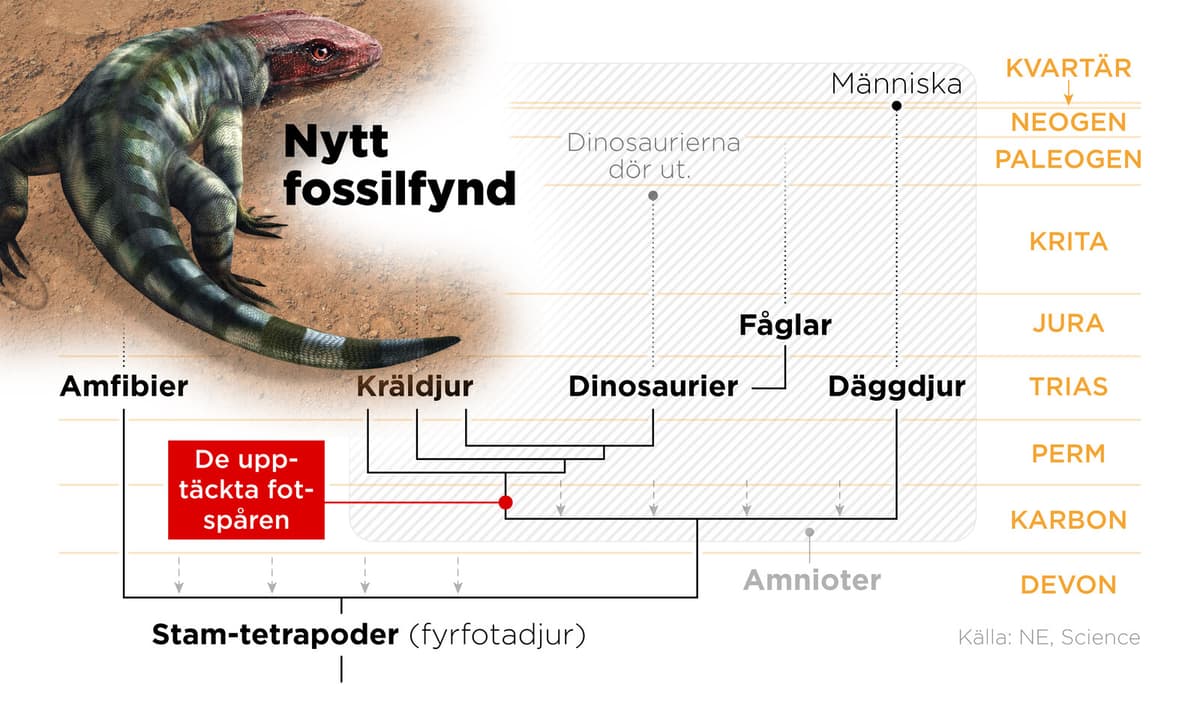

This is long before the dinosaurs, just after the first vertebrates crawled onto land. Here, they branch out into amniotes – which mammals, dinosaurs, birds, and reptiles come from – and amphibians. The age is extra important in this context. The tracks are namely 35 million years older than all other amniote finds.

They look roughly like the footprints of a lizard today, with fairly long toes and with clear claws that leave marks in the sediment. Claws are, after all, something that amniotes have invented. You don't really find claws in other groups of land vertebrates, says Per Ahlberg.

If amniotes existed so early, it means that advanced land vertebrates must have emerged earlier than researchers thought, when the first vertebrates crawled onto land during the so-called Devon period.

So, the footprints show that amniotes are older than researchers previously thought, and that it's about relatively advanced animals.

It's unlikely that there was just one species wandering around there. Likely, we have a whole fauna of different animals here, says he and continues:

But the thing is that we haven't found them yet."

"Would be wonderful"

It sounds like big conclusions to draw from a few tracks, and Per Ahlberg expects the study to receive from peers. Where the stone block was found, many fish fossil finds have been made. Maybe there are hiding more tracks from other land-dwelling creatures.

More footprints would be fantastic. Skeletal material would also be wonderful. It would give a whole new dimension, says he.

The footprints reveal a lot in themselves:

We can see how they move.. But the only part of the animal we actually get to see is the soles. And that's a bit limiting.

The footprints were discovered on a stone block in Snowy Plains Formation in Australia.

By comparing the footprints with the bandy-legged varan, which has similar feet, researchers have estimated that the animals were about 80 centimeters long, although it's unclear how long the tail and head were.

The find suggests that the animal group amniotes (which includes reptiles, birds, and mammals) is older than thought and that the development from water-dwelling animals to four-footed animals (land vertebrates) occurred faster than previously thought.

The study is published in the journal Nature.