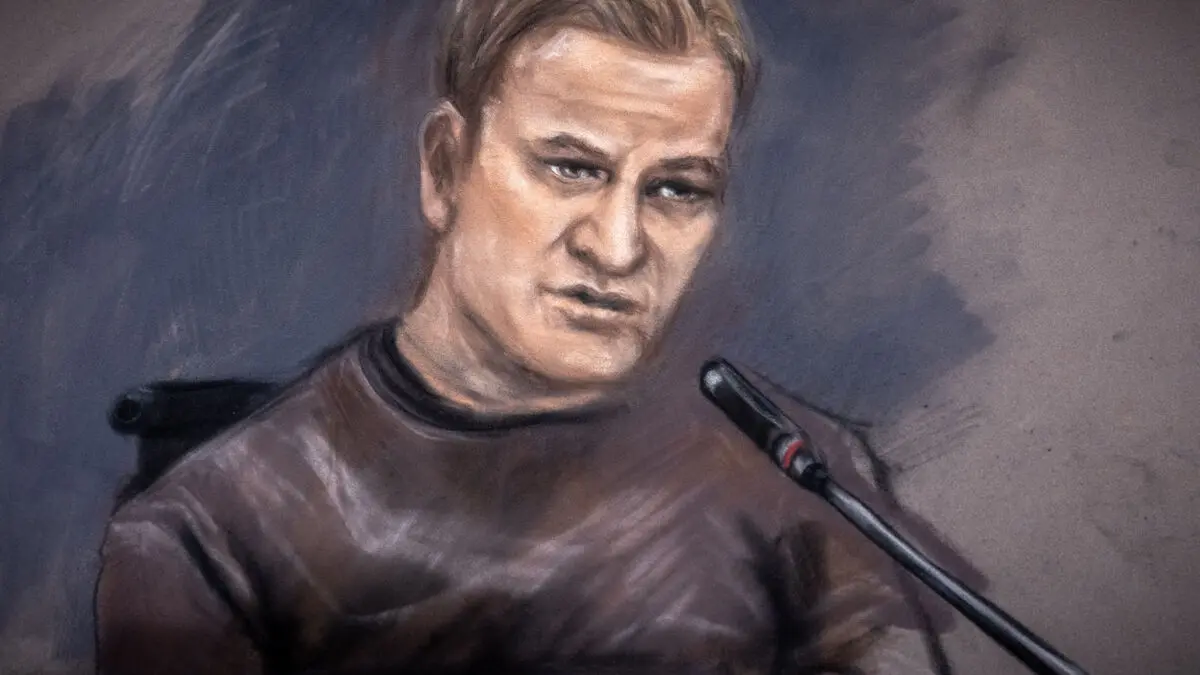

Marco Rubio looked tense as he sat in front of his senator colleagues in the fully occupied foreign affairs committee. It was now that it would be decided whether he had their support for the appointment as foreign minister.

So he took the floor and began to describe in vivid terms the US-led world order that had prevailed after World War II: One where prosperity had increased, democracies had flourished, alliances had been created with Europe and Southeast Asia, and the Berlin Wall had finally fallen. Then, a form of consensus emerged around the idea that a "liberal world order" for "global citizens" would replace interest-driven national foreign policy.

A dramatic pause.

It was not just a fantasy. It was a dangerous illusion.

A weapon?

The room fell completely silent. Everyone's eyes rested on Rubio as he stated that the "almost religious" faith in free trade was harming the US economy, the middle and working classes.

The global world order that has prevailed after World War II is not just obsolete. It is a weapon used against us.

The future foreign minister promised that his homeland was now his only and top priority – that all State Department initiatives would either make the US safer, stronger, or more successful. The argumentation had clear echoes of Donald Trump's campaign speeches.

A useful rhetoric, notes Björn Fägersten, senior researcher at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs' Europe Program and the analysis firm Politea.

Trump believes that the US cannot afford to scatter money on general world improvement and act as a world police. And one does not appreciate the benefits that global institutions provide.

New "hyper-competition"

The attitude shift was clear already during Donald Trump's first term: The World Health Organization (WHO), which Trump has now withdrawn the US from, was criticized for its COVID-19 management. The global climate agreement concluded in Paris was dismissed. The International Criminal Court was described as a threat to the US and its ally Israel.

In reality, we have been on our way to leaving the liberal, global world order for a while – we are in a transition phase. The US is making a big bet on an alternative order, and the question is what to call it, reasons Fägersten.

EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen seems to have put her label on it. In a speech to the EU ambassadors recently, she said that the idea of close cooperation and hyper-globalization is outdated. Instead, the world is entering an era of "hyper-competition and hyper-transactional geopolitics" where the EU must defend its values and interests, according to von der Leyen.

Threats and deals

From that perspective, it is not surprising that businessman and real estate magnate Trump has started his second term by threatening China, Mexico, and Canada with tariffs, claiming that he wants to annex Greenland and Canada, and stating that the US should "take over" the Gaza Strip. Meanwhile, Washington has backed out of international collaborations, shut down the aid agency USAID, and announced that an agreement on rare Ukrainian soil metals is desirable if the war-torn country is to receive continued aid.

It is a balancing act. At the same time as one looks after one's own house, one wants to maintain the role as the only superpower and have world dominance, notes Fägersten.

The course change is not popular everywhere. World leaders are sharpening their knives behind closed doors. At home in the US, loud protests are being held.

But Team Trump is selling the new world order with all possible means. Shortly before the president took office, his son and namesake Donald Jr. visited Greenland and let himself be photographed with enthusiasts in red caps. And as soon as Marco Rubio got the green light as foreign minister, he set off for Panama, which Trump has put under heavy pressure. This with threats to take back the Panama Canal, which the US handed over to the country in 1999, and which Trump claims China has gained too much influence over. The other day, Rubio announced that American authorities' ships can now sail through the canal for free – something Panama completely denies.

Like the Cold War?

China runs like a red thread through the new US doctrine, both militarily and economically. Trump says he is in no hurry to talk to President Xi Jinping, despite Beijing protesting against the broad tariffs of 10 percent he has announced on Chinese goods. When it comes to Beijing, the situation is now not entirely unlike the Cold War, notes Fägersten.

Rubio and his gang are China hawks. They want to have a number of core allies, they do not necessarily have to be democracies, that will join the US gang rather than China's, he says.

Trump has a well-documented fondness for authoritarian leaders, during his previous term, he met with Xi Jinping, North Korea's dictator Kim Jong-Un, and Russia's President Vladimir Putin. It is not impossible that the newly elected president will try to make a "deal" with one of them, agreements that will then overshadow formal politics.

Want to be loyal

In Europe, which has long seen itself as the US's closest ally and where many countries are NATO members, many are scratching their heads and trying to interpret "the law of the jungle". Trump has already hinted that Europe buys too few cars from his homeland and that tariffs are to be expected.

It is complex. On the one hand, the EU wants to be loyal to the US, on the other hand, it is preparing for trade war. And within the EU, one also wants to save parts of the institutional order. Globalization is not dead, but it will function according to new geopolitical premises, says Björn Fägersten.

The rule-based world order is sometimes called the Western, liberal world order. It is based on certain values, norms, institutions, and rules that were created to govern states' actions globally.

Among these are the UN Charter's formulation on the equality of nations and the prohibition of violence and threats of violence between states. The principles of human rights, international humanitarian law (including the four Geneva Conventions on the laws of war), international criminal law, and treaty law are important.

The rule-based world order was developed after the end of World War II. The US's former foreign minister Antony Blinken has described it as a "system of laws, agreements, principles, and institutions that the world built together after two world wars to govern relations between countries, prevent conflicts, and uphold all human rights".

Sources: The Royal Swedish Academy of War Sciences, the Government Offices, and the British Parliament