In December, OECD published the results of a global competence test among adults in 31 countries. For Sweden's part, the result is uplifting: Sweden ranks third, with only Finland and Japan ahead. In the oldest age group, 55+, Sweden is the best.

It's a very positive result, says Andreas Schleicher.

He has long followed Swedish education and, as responsible for OECD's PISA measurements among 15-year-olds, has analyzed both the ups and downs of the Swedish results. Last time, in 2023, it was more about a decline.

Can be developed

The more positive result in the "adult PISA", or PIAAC as the study is called, Schleicher explains with a culture in Sweden of courses, further education, and competence enhancement.

Many countries struggle to get more older people to engage in learning. In Sweden, there is an understanding of lifelong learning from an early age. There is also an insight that good workplaces provide good opportunities for further education, says Andreas Schleicher.

The opportunities for development are greater in Sweden than in both Finland and Japan, according to Schleicher.

Japanese workplaces are bad at utilizing employees' competencies, many never get a chance to show their skills. A bit of that is also visible in Finland. Sweden is better in that it thinks less in terms of formal exams and more in terms of what people know and can do.

Like a ten-year-old

But his picture is mixed. The fact that 12 percent of Swedish adults – and 15 percent of the youngest adults – have insufficient reading skills is alarming:

In today's society, you need to be able to navigate among ambiguities, be able to distinguish facts from opinions. Swedes are still relatively good at this, but reading skills should have improved considering the increased demands. It's too large a proportion that reads at a ten-year-old's level, says Schleicher.

When the reading skills among Swedish 15-year-olds showed a decline in the latest PISA measurement, Andreas Schleicher criticized the Swedish school system for having become a service institution, with students as passive consumers. He then called for more engagement in the classrooms, and he still does.

For the adult workforce, it's going well because workplaces are very competence-oriented and fantastic learning places. I think the school system has gone in the opposite direction for many years – learning has lost its status, he says.

PIAAC stands for Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competences and is initiated by OECD. It has been conducted twice.

SCB is responsible for the Swedish implementation.

Reading, arithmetic, and problem-solving skills are included in the test.

160,000 people born 1957–2006 in 31 countries/regions participated in PIAAC 2023.

In the Swedish part, 3,700 people participated.

Source: SCB

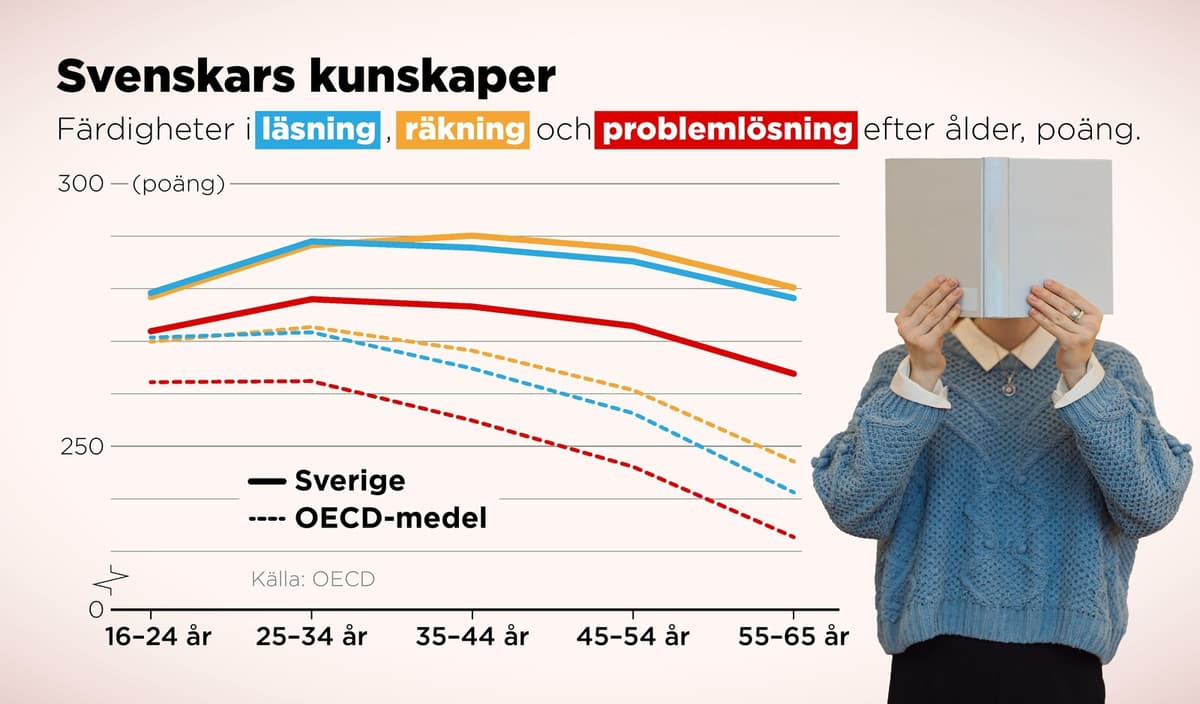

PIAAC shows that the competence level is highest in the age group 25-34 years, both in Sweden and internationally. Lowest is in the youngest and oldest age groups.

This is explained by the fact that many 16–24-year-olds have not yet completed their studies and that 55–65-year-olds on average have a lower education level than younger generations.

In PIAAC 2023, Sweden, with all age groups, had 284 points in reading comprehension, the third highest after Finland (296) and Japan (289).

But in the oldest age group, 55+, Sweden had the highest score of all participating countries: 278. Finland had 271 and Japan 268.

Sweden also had the lowest proportion of low-performing 55+ of all countries: 11 percent. Finland had 18 and Japan 19 percent.

The same pattern is seen in arithmetic and problem-solving: In the oldest age group, Sweden had the highest score of all and the lowest proportion of low-performing.

Source: OECD and SCB