The situation within Swedish forensic psychiatry is described as tougher than ever. Nationally, the occupancy rate is far above 100 percent. In some regions, the occupancy rate has reached up to 150 percent at times this year.

This creates a high pressure on the staff, with more patients per caregiver than normal.

You don't increase the staff according to the number of patients. There is no law governing basic staffing, says Sofia Risku, workplace representative and safety representative at Kommunal at Rågården forensic psychiatry in Gunnilse, Gothenburg.

In the department where she works, they have been forced to convert two rooms to solve the overcrowding. These are rooms without showers or toilets, and one of the staff toilets is now being used by patients.

Emergency situations

The decrease in staff density as clinics become overcrowded also means that they are less equipped to handle emergency situations, she says.

If there is a threat and violence situation and two people respond to the alarm, there should be two people left. Then you don't count on someone being in the toilet, but it's planned as tightly as possible.

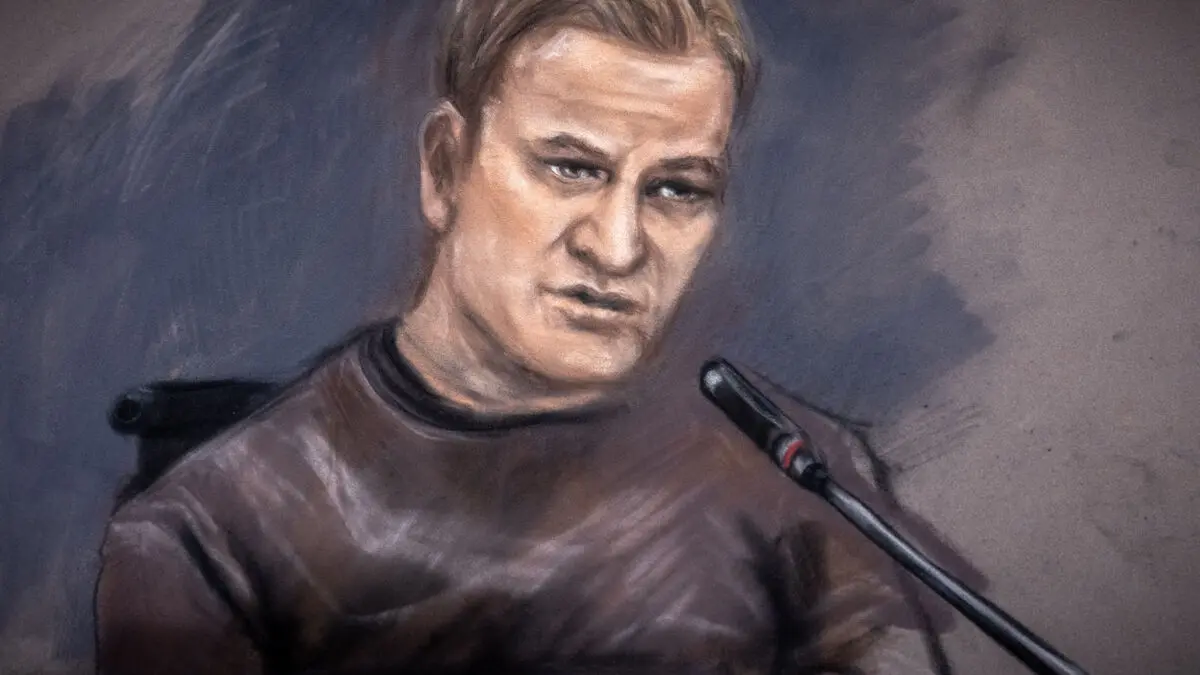

Even at the clinic in Vadstena, it's overcrowded. There, they have had to convert conversation rooms into patient rooms in emergency situations, says chief safety representative Oliver Lindgren.

It's "problem-solving deluxe", he says.

The occupancy rate also makes it harder to move patients to other more open departments, so they can progress in their care.

It can take a very long time from when a patient is ready to move to when they can do it. Patients become frustrated about having to wait and nothing happens.

This can affect the work environment, says Lindgren.

It creates problems both for them and for us, where it can lead to more threats and violence when they become frustrated.

No quick solution

Neither Oliver Lindgren nor Sofia Risku sees a quick solution in sight. Treatment times need to be shortened and forensic psychiatry needs to be expanded.

Both wish that politicians could focus as much on this end of the justice system as on the others. Oliver Lindgren compares it to the investments in the Prison and Probation Service.

There, they just build new houses. But the need within forensic psychiatry won't decrease either.

Sofia Risku hopes that those working on the ground will be heard, and that decisions won't be made over their heads.

I can only hope that we somehow get more resources and think more long-term.

Those who suffer from a serious mental disorder and commit a crime should be sentenced to forensic psychiatric care. For most who are sentenced to forensic psychiatric care, a so-called special release assessment (SUP) is also decided.

SUP means that the administrative court, not the chief physician, decides when a patient is discharged. The court shall, in those cases, make a comprehensive assessment of the person's situation, taking into account the risk of reoffending.

In 2023, forensic psychiatric care was the main sentence in 331 verdicts. Compared to 2014, the number of verdicts with forensic psychiatric care as the main sentence has increased by 27 percent. Treatment times have also increased.

In 2023, over 2,000 people were cared for within forensic psychiatric inpatient care.

Source: Brå, SKR