Over the past few weeks, hundreds of Sudanese have been stopped in boats on the Atlantic.

They have left their war-torn homeland in northeastern Africa and crossed the entire continent – with their sights set on the Canary Islands. It is increasingly appearing as a possible "back door" to Europe, as it has become increasingly difficult to cross the Mediterranean in the north.

The Sudanese fleeing westward are becoming more and more numerous, but they are still only a small part of at least 12 million people fleeing the raging war and humanitarian disaster in Sudan.

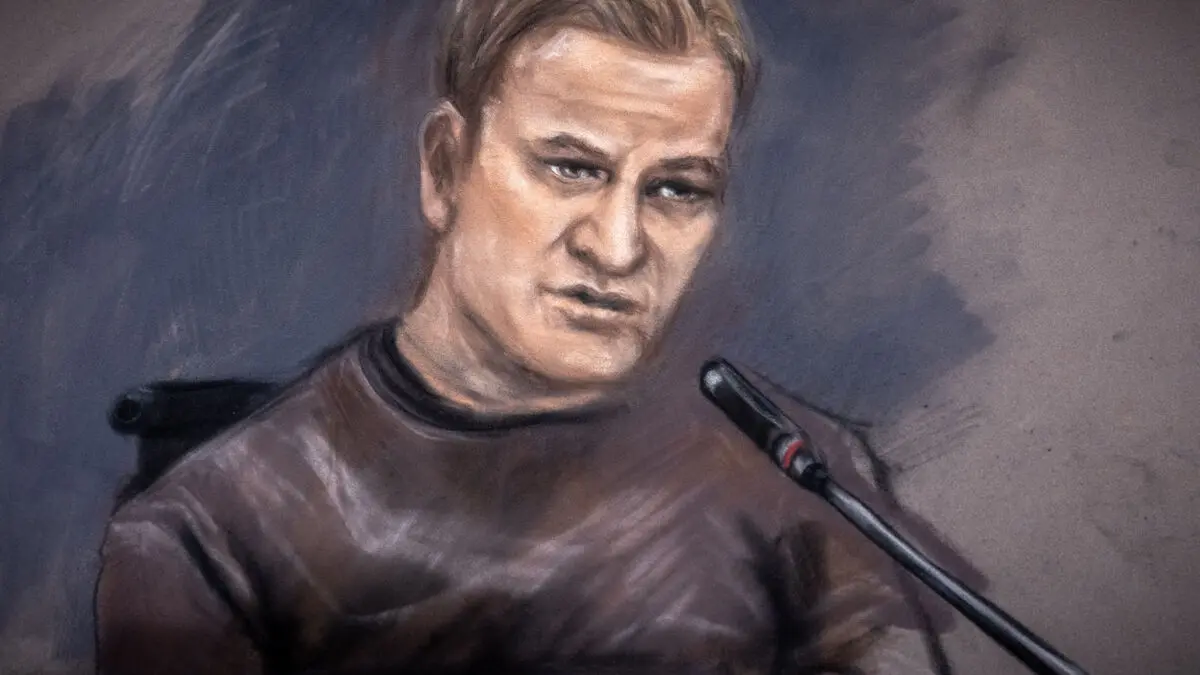

It's not just about what's happening in Sudan, because it doesn't stop there, but spills over into its neighboring countries, says Abdouraouf Gnon-Konde, who is the highest chief for the UN refugee agency UNHCR's work in western and central Africa.

Receiving more and more

Hundreds of thousands of people have crossed Sudan's western border and ended up in Chad. The influx continues, as the civil war is not subsiding. By the end of this year, Chad may have received around 1.5 million people, according to Abdouraouf Gnon-Konde.

Chad, which has its own problems, has opened its borders. Chad has chosen not only to welcome them to camps there, but into society, says the UNHCR chief.

There are already many people who have fled violence in the Central African Republic, Cameroon, and northern Nigeria. In addition, several hundred thousand Chadian citizens who have returned from conflict-ridden countries where they were living, emphasizes Gnon-Konde.

How can one expect a country with 17 million inhabitants, one of the poorest countries, which has already been so generous, to provide so much land and welcome everyone? They can only give what they have.

Support more than halved

Abdouraouf Gnon-Konde is visiting Sweden, Denmark, and several other countries at a time when the rug has been pulled out from under the UN agencies' work worldwide. His department's work in 19 countries has so far been financed to 60 percent by the USA.

The news that American aid is being stopped has already affected around half a million people, according to Gnon-Konde. Exceptions are being made for at least a short time ahead for life-saving efforts.

If this aid is permanently frozen, we can expect two million to be affected, he says.

Four out of five fleeing Sudanese are under 25 years old, according to the UNHCR chief. Many live in rural areas or established tent camps. Some look ahead and want to move on, then with need towards Africa's Atlantic coast far to the west.

They don't just need life-saving efforts, but they need to be given opportunities that allow them to stay in areas near their homes, despite all the challenges they face.

Kicked out into the desert

The EU is trying to stop all migrant boats on the Mediterranean and has agreements with countries in North Africa to ensure that the boats do not leave the harbor. Despite this, more and more Sudanese are seeking to head towards the Mediterranean and countries such as Libya and Tunisia.

It has been repeatedly reported and warned that hundreds of migrants are being detained and pushed back into the desert south. Masses of people have died in the Sahara, sometimes more than those who have drowned in the Mediterranean.

The problems are temporarily swept under the rug from Europe's threshold and land on poor countries further south, according to Abdouraouf Gnon-Konde. There, hard-ruled Chad appears relatively stable, only against the backdrop of jihadist attacks, military coups, and crises in the region.

In September, I visited a humanitarian facility in Niger, at the border with Libya. The largest group there, around 2,000 people, was Sudanese. It shows that they don't stay in Chad or other neighboring countries. They leave our camps and travel to other countries, probably in hopes of better living conditions.

Wants to help on the spot

On the way west towards the Atlantic and the Canary Islands, they meet Malians, Syrians, Afghans, and others who have the same goal. The UNHCR chief wishes that the EU makes greater commitments along the growing refugee routes.

It is possible to help these people on the spot in the region, according to Abdouraouf Gnon-Konde. He notes that thousands of Central Africans, Cameroonians, and Nigerians who have received protection in Chad in recent years have been able to return home.

If we don't support these countries, people will seek to go even further.

The war in Sudan broke out in April 2023, when a split occurred within a military junta that had taken power a couple of years after the fall of long-time dictator Omar al-Bashir.

On one side stands General Abd al-Fattah al-Burhan, who commands the army, and on the other, his former deputy Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, who leads the so-called RSF militia.

Tens of thousands of people have been killed in the war. More than 14 million people have been driven into flight. The country has in practice been divided: the army controls areas in the north and east, and the RSF with coordinated groups controls areas in the west and south. The capital Khartoum is also divided and heavily contested.

Both parties have repeatedly been accused of war crimes.

The RSF has its origins in the notorious janjaweed militias, which were sent out under al-Bashir's rule to spread terror and crush the uprising in Darfur in western Sudan in the early 2000s.

Chad is located in central Africa and stretches north over the Sahara Desert's steppes. It lacks a coastline and is surrounded by mountains in all directions except in the west. Its area is approximately three times that of Sweden.

There live around 18 million inhabitants who belong to around 200 different ethnic groups, with Arabs making up the largest. Hundreds of thousands of people are also there after fleeing various conflicts in the region.

Chad became independent from the colonial power France in 1960 and is today one of the poorest countries in the world.

The country was ruled for over 30 years by President Idriss Déby Itno, who came to power through a military coup in 1990. When he was killed in battle with rebels in 2021, his son Mahamat Idriss Déby took over. Their regime has always held political opposition and media in a tight grip.

Besides that, the country has suffered from ethnic tensions and regular attacks from jihadist groups such as Boko Haram and others.