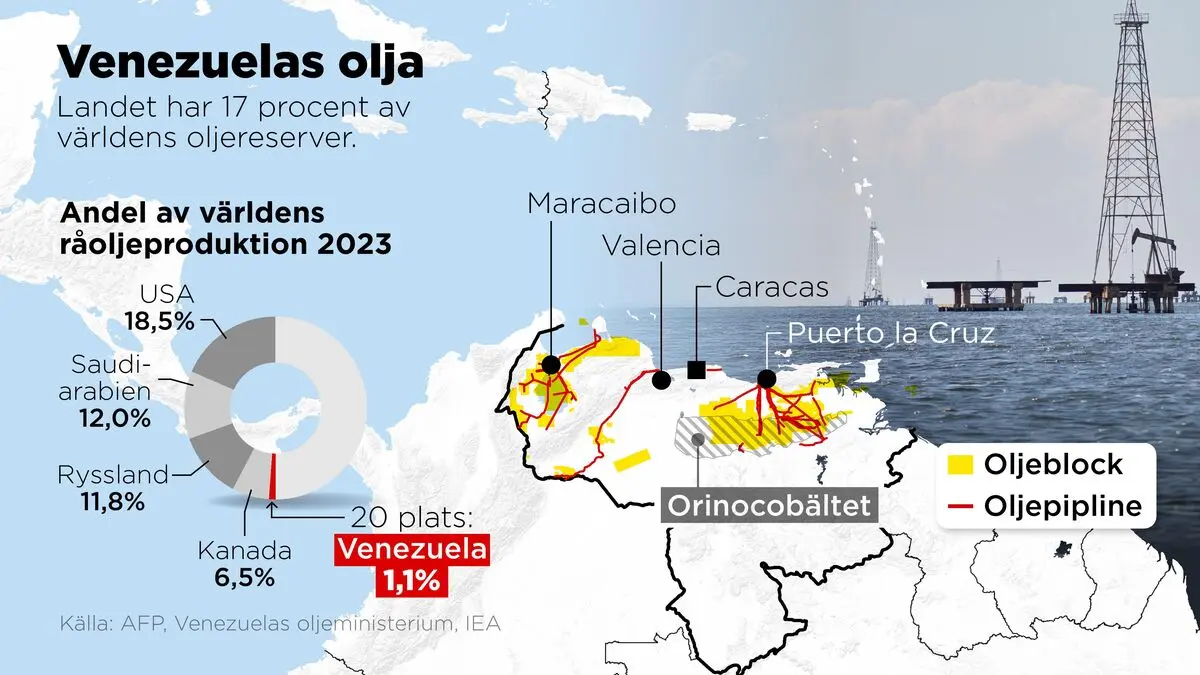

US President Donald Trump sees untapped potential when he looks at Venezuela's oil fields. Venezuela has 17 percent of the world's reserves, but the country accounts for only 1 percent of production.

The United States wants to take control and revive the country's oil sector, with the help of American oil giants.

Difficult to handle

But experts are skeptical. One problem is that the equipment is old and worn out. When Venezuela nationalized its reserves, much expertise left the country, and the revenues were not reinvested in the facilities, says Thina Saltvedt, chief analyst for sustainability and energy at Nordea. Production has fallen 70 percent since 2016.

Maintenance has been very poor, and this means that infrastructure, production units, pipelines, ports, ships - everything is actually in very poor condition.

Tripling production to 3 million barrels a day would require $183 billion and take 15 years, according to an analysis from Rystad Energy.

The second problem is the oil itself - a thick, tar-like variety.

That simply makes it difficult to produce, difficult to ship to refineries and difficult to refine, says Saltvedt.

“The worst oil in the world”

Trump himself has

Venezuela's oil as "the dirtiest, probably the worst oil anywhere in the world."Adam Brandt, a Stanford professor who studies emissions from different energy sources, writes in an email to TT that this type of oil requires heat to be extracted from the ground, which leads to more emissions.

At night, the oil fields are lit up by flames, more visible from space than the lights of the capital Caracas, as valuable natural gas burns up because it cannot be handled. Much of the methane is released directly into the atmosphere.

"The crude oil is of poor quality, which increases the energy consumption during refining. Refining heavy crude oil leads to more energy and hydrogen consumption, and this is done in the most sophisticated refineries built to process challenging crude oil."

A barrel from Venezuela's Orinoco Belt is estimated to lead to 900 times more greenhouse gas emissions than a barrel from Norway's Johan Sverdrup, according to S&P Global Platts Analytics.

In addition, there is concern from the oil giants about regulations and the politically unstable situation in Venezuela.

"We've had our assets there seized twice, so you can imagine going in a third time would require some significant changes. Today it's uninvestable," Exxon Mobil CEO Darren Woods said during a White House meeting.