In months, hundreds, perhaps thousands of Lebanese people unknowingly carried small, ticking bombs in their pockets.

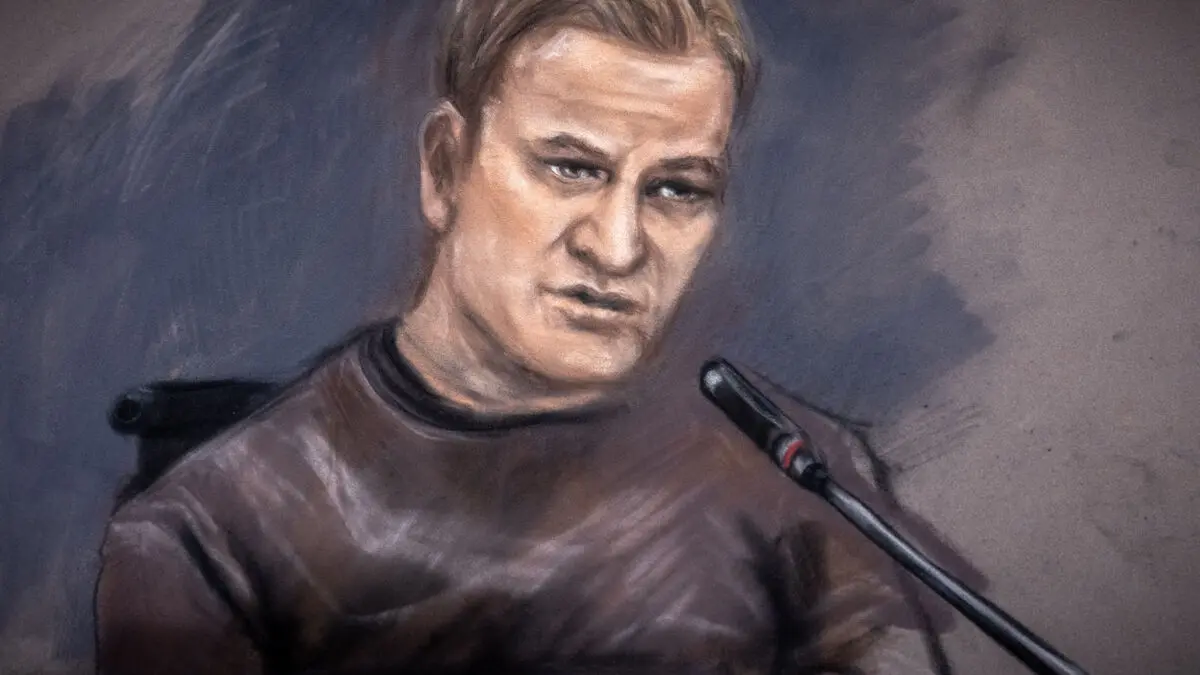

This is not the first time seemingly ordinary objects have been transformed into weapons. But the scale of the attacks in Lebanon is unprecedented, according to Jann Kleffner, professor of international law at the Defense University in Stockholm. This makes the legal issues more complex.

Simply put, you can only direct attacks against military targets – not civilians. Here, it's difficult to know, says Kleffner, pointing out that Hezbollah not only consists of armed forces but also has a strong role in politics and social life in Lebanon.

The approach inevitably puts innocent people in the line of fire, several analysts have claimed after the attacks. The laws of war, which are based on the four Geneva Conventions from 1949, state that civilians must be protected.

The question is what measures have been taken to direct the attacks against legitimate targets, says Kleffner.

Difficult to know

According to humanitarian law, the military significance of an attack must also be "in proportion" to the risks civilians are exposed to.

If 80 percent of the victims are armed forces and you know that – then the legal analysis becomes completely different than if you had just sent out thousands of mined seekers on the open market.

The fact that the attacks were carried out remotely makes the whole thing even more complex. When hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people-searchers and walkie-talkies explode almost simultaneously, it's hardly possible for the person pressing the button to know where or in whose hands all the units are, says Kleffner.

We've seen pictures of seekers exploding in the middle of a market. How much did the operators know about where the people in question were at the time? Can you know that? In my eyes, it's almost impossible.

"Ticking bomb"

The attack raises concerns about future warfare in a world where we are becoming increasingly dependent on digital technology. Yousef Munayyer, a Palestinian-American political analyst, claimed on Tuesday that the attack opens "a dangerous Pandora's box".

"Almost every person is walking around as a ticking bomb. It won't take long before this technology is used by many actors", he wrote on X.

How relevant are the laws of war when digital technology becomes a weapon?

The rules that exist are quite general and quite vague. Sometimes it's a disadvantage, but often an advantage, as it makes them easy to apply to new phenomena, says Jann Kleffner.

Civilians must not be attacked in armed conflicts and must be protected, according to international principles that the world community has agreed upon.

The laws of war – formally international humanitarian law – aim to spare combatants, the wounded, prisoners of war, and civilians from unnecessary suffering. The core consists of the four Geneva Conventions from 1949, which have been ratified by nearly 200 states. Both state and non-state actors are bound by the laws.

Key words are distinction (separation of civilians and combatants), proportionality (the military significance of an attack must be weighed against the risks it poses to civilians), and precaution (all parties must take all possible precautions to ensure that attacks are only directed against military targets).

The fact that non-civilian persons are present among civilians does not mean that the group as a whole can be considered a legitimate target. The civilian population must not be used as so-called human shields to defend against attacks.

The special protection emblem of the medical service must be respected, and the warring parties must do what they can to facilitate humanitarian efforts.

Source: UN, Red Cross, and National Encyclopedia