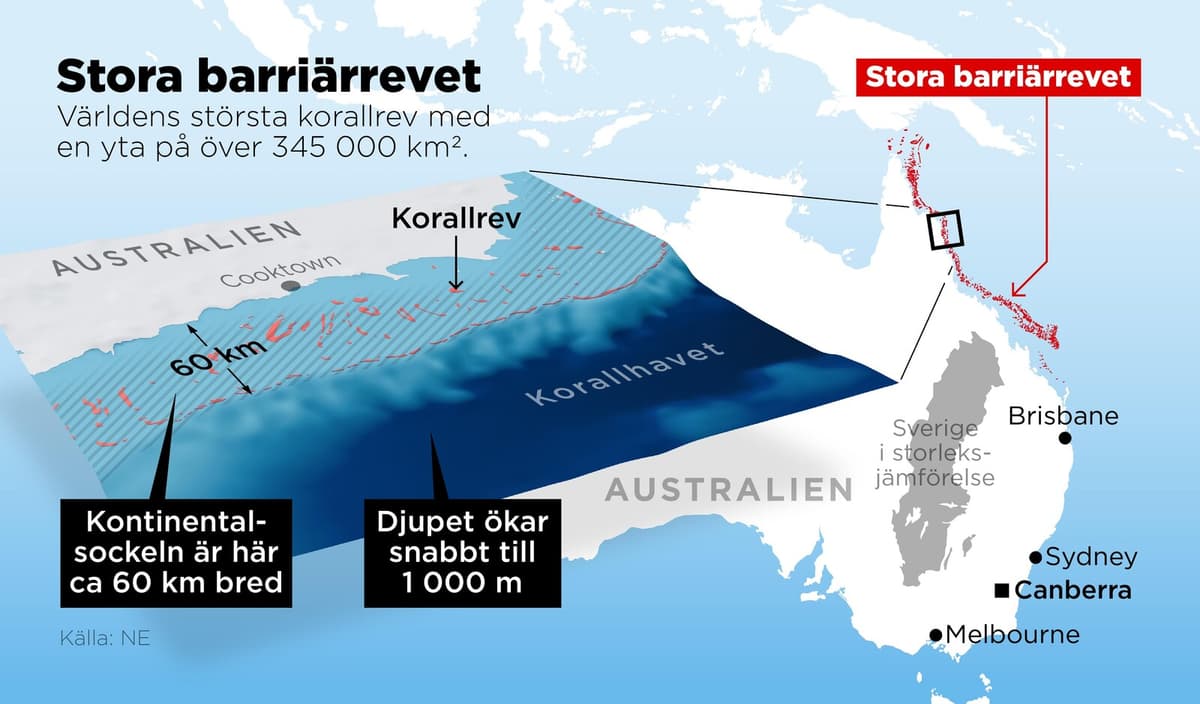

The Great Barrier Reef stretches over 345,000 square kilometers, equivalent to three-quarters of Sweden. In addition to the coral itself, the Great Barrier Reef is home to thousands of different animals and plants, including several hundred bird species.

Other barrier reefs around the world, such as those off Belize and New Caledonia, are also breathtakingly beautiful and impressive – but extremely smaller. Why did such a mega-reef form just off Australia's northeast coast? How did it happen, and when did it happen?

Part of the answers have now been found by researchers at Christian Albrechts University (CAU) in Kiel, Germany, together with colleagues in Graz, Austria, and Southampton, England. With a new measurement method called tex86, they have been able to map temperatures and other conditions several hundred thousand years back in time through core samples from the barrier reef area.

Millions of years

Australia is located near the seismic "Ring of Fire" in the Pacific Ocean, but is geologically much more stable. The same applies to the approximately 60-kilometer-wide "shelf" that protrudes from the current Queensland coast to the boundary where the seafloor drops from just a few tens of meters deep to 1,000 meters or more.

Water levels have varied greatly, but from time to time, corals and fish have thrived here in a relatively protected environment for millions of years. CAU researchers are now publishing measurements that go back about a million years, and they show that water temperatures were long relatively low, often between 20-25 degrees.

"The corals grew slower at those temperatures, which prevented the small coral reefs that existed at the time from expanding into a larger barrier reef," writes CAU in a press release.

Built up

But then, about 700,000 years ago, the heat in the sea reached a kind of magical limit. Summer temperatures stabilized in the range of 26 to 29 degrees, which proved perfect. It's quite close to the maximum heat level that corals thrive in, but since the values remained stable for long periods, the "frames" for a gigantic barrier reef could be built up in peace and quiet. Even during the epochs when water levels dropped, the reef's foundations remained, and could be built upon when the water rose again.

Previously, it has been speculated that sea levels or sediment washed out from land were more controlling in the development, but the Kiel-led study changes the picture.

"For the first time, we have been able to prove that higher summer temperatures along Australia's coast were decisive for the formation of the Great Barrier Reef," says CAU researcher Benjamin Petrick, the study's lead author, according to the press release.

25-30 perfect

But no equal sign is set between higher temperatures and flourishing reefs – unfortunately for the Great Barrier Reef, now that human-induced climate change is also ravaging the oceans.

Last month, a research report showed that water temperatures at the Great Barrier Reef over the past decade have been higher than at any other time since at least the beginning of the 17th century.

So relatively rapid temperature changes, whether up or down, are bad for the reefs, is the conclusion. There is a perfect level somewhere between 25 and 30 degrees, and "our data suggest that long periods of suitable temperatures are a requirement for the Great Barrier Reef to develop and maintain itself," the researchers write in a report now published in the journal Science Advances.

A barrier reef is called so because it lies along a coast and forms a kind of barrier between the shoreline and the deeper sea further out.

In Australia's case, it's about 3,000 smaller reefs and 900 islands that form a "string of pearls" along the Coral Sea's edge outside the state of Queensland. In some places, the water is so shallow that it's barely possible to snorkel there, and at its deepest, it's about 60 meters to the seafloor at the Barrier Reef.

Tropical coral reefs cannot lie much deeper, as they need light to thrive. There are also cold-water reefs that can lie further down in the oceans, but they are not as spectacular. And often not as large – the world's largest, the Røst Reef in Norway, spreads out over about 100 square kilometers.

A reef's base consists of calcium from dead corals' skeletons. It therefore takes a very long time, hundreds of thousands of years, for a large reef to build up.

Corals belong to the phylum cnidarians, together with, among other things, jellyfish. The Great Barrier Reef is sometimes described as the world's largest living organism.