There is a saying that if two problems run along the same timeline, they can have a negative impact on each other, even if they are not related, says Nikola Zlatkov Kolev, researcher at the Department of Molecular Biology at Umeå University.

Our use of plastic and antibiotics has long run parallel. A study led from Umeå University shows that nanoparticles that enter the body can impair the effect of antibiotics.

What we are facing now is two major problems that are merging with each other.

Nanoplastics are plastic particles that are smaller than one thousandth of a millimeter. They can float freely in the air and enter the body.

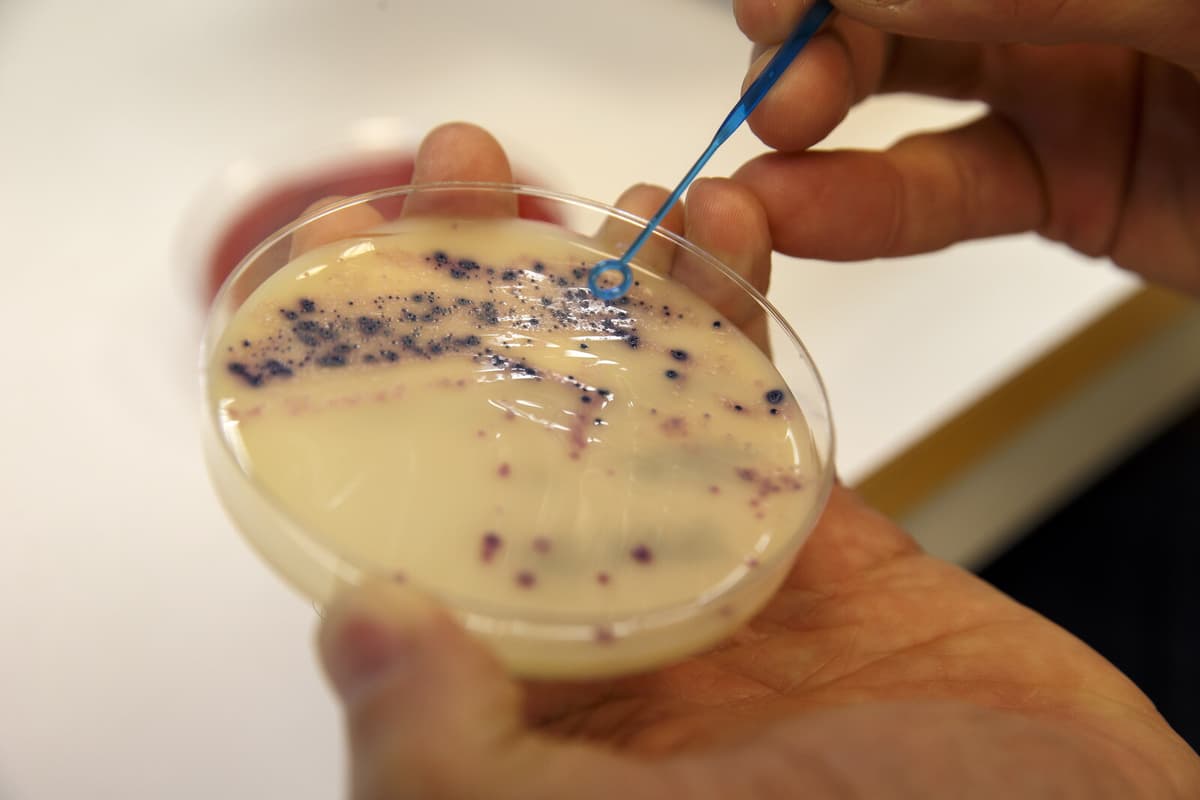

The researchers looked at how some of the most common nanoparticles interacted with the antibiotic tetracycline and found that the plastic absorbed the antibiotic.

Tetracycline was bound to the plastic and could therefore not kill bacteria, says Nikola Zlatkov Kolev, who led the sub-study on the binding to antibiotics.

Tetracycline is an antibiotic used primarily against various serious respiratory diseases.

The binding was particularly strong to nanoparticle nylon, one of the substances most commonly found in indoor air nanoparticles.

There is a risk that it could lead to the antibiotic following the nanoplastic in the bloodstream and ending up in the wrong places in the body. This, in turn, could reduce the targeted effect of the antibiotic and lead to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, a development that researchers see as very worrying.

In essence, we are facing a new kind of resistance.

Microplastics are small pieces up to five millimeters. Nanoplastics are even smaller pieces, less than 100 nanometers.

Previously, it has been established that plastics cause diseases in birds and fish – gastrointestinal and reproductive problems, inflammation, and neurological disorders.

Although no large-scale studies have been conducted on humans, the same trend has been seen in us. Plastics have been found in, among other things, lungs, breast milk, blood, and brains.