In the week, the Riksdag reopened after the summer break, and the government is entering what Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson (M) describes as the "second half" of the term.

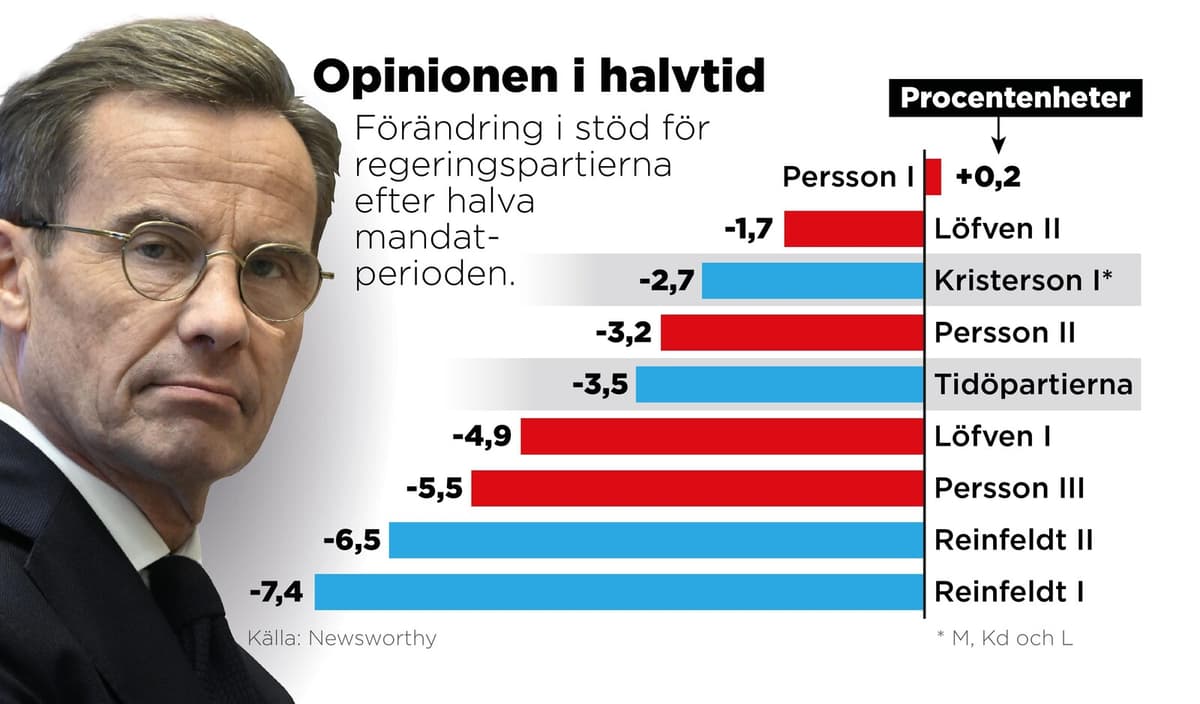

It does so with significantly weaker opinion support than when it took over two years ago. The opinion website "Ada poll of polls", which compiles and weighs various opinion polls, now shows that Kristersson's government (M, KD, L) has 26.4 percent support, compared to 29.1 percent two years ago – a decline of 2.7 percentage points.

If one includes the supporting party Sweden Democrats, the decline is 3.5 percentage points.

Not unique

The decline is, however, not unique in a historical perspective. Almost all previous governments in recent decades have lost support when they reached the "half-time break". This is a clear difference from how it looked in the 50s and 60s, notes Henrik Ekengren Oscarsson, professor of political science at the University of Gothenburg:

Today's voters have stopped "rewarding" sitting governments, it's instead very much about punishment. There are several explanations, he says to TT.

Among these, he mentions, among other things, the role of the media, as well as the prevailing decision-making tempo.

The media have become better at scrutinizing sitting governments. The spotlight is stronger, simply. Opposition parties have also become better and perform better in that role, while a government today makes tens of thousands more decisions during a term than in the 60s.

And the more decisions you make – the more risks you also take of stepping on toes.

Tough start

For Ulf Kristersson, it was also a tough start when inflation, electricity costs, and interest rates soared. An immediate opinion decline is not unique, notes Henrik Ekengren Oscarsson.

You start losing directly to 85-90 percent of the support you had in the election and then it goes downhill. Then you usually end up at an average of 90 percent.

So what speaks in favor of Ulf Kristersson and his government when it's time for elections again? Maybe history. We have to go back several decades to find a sitting government that hasn't been re-elected – at least once.

Henrik Ekengren Oscarsson also notes that after economically tough years, the turnaround may be on its way, something that can help a sitting government.

It may be that you go to the election in 2026 with an economy where most things point upwards. Looking at how voters behave around the world, the economy is always included, he says.